Cohabitive games so far

A cohabitive game1 is a partially cooperative, partially competitive multiplayer game that provides an anarchic dojo for development in applied cooperative bargaining, or negotiation.

Applied cooperative bargaining isn't currently taught, despite being an infrastructural literacy for peace, trade, democracy or any other form of pluralism. We suffer for that. There are many good board games that come close to meeting the criteria of a cohabitive game today, but they all2 miss in one way or another, forbidding sophisticated negotiation from being practiced.

So, over the past couple of years, we've been gradually and irregularly designing and playtesting the first2 cohabitive boardgame, which for now we can call Difference and Peace Peacewager 1, or P1. This article explains why we think this new genre is important, how it's been going, what we've learned, and where we should go next.

I hope that cohabitive games will aid both laypeople and theorists in developing cooperative bargaining as theory, practice and culture, but I also expect these games to just be more fun than purely cooperative or purely competitive games, supporting livelier dialog, and a wider variety of interesting strategic relationships and dynamics.

A salve for strife and waste

In these primal lands

It can be found

Motivation

We all need it

In our formative years, we make many choices, but we hold no power, so most of us don't receive experience in negotiation until we're well into adulthood. Natural experiences of conflict tend to be messy, ambiguous, with high stakes, forbidding free experimentation. It's very much not conducive to learning. So let's make games that foster clear, low-stakes scenarios where negotiation can be learned.

Democracy requires this of us. When we are not taught to recognize acceptable compromise, we wont be able to recognize legitimate political outcomes either. Most suffering comes from that.

A person without negotiation skills will lack faith in the possibility of peaceful resolution of conflict. They will consummate either as an eliminationist, or they will live in denial of conflict, they will hide it, hide from it. They won't have an appropriate sense of when to stand their ground or when to capitulate. The social norms of their cliques will expect and demand passivity, compliance, and avoidance. Conflicts will fester. When conflicts inevitably play out, the less acknowledged, the messier they will be. Instead of words and deals, death or withering and waste. We cannot live together like this.

We must teach negotiation, the graceful reckoning with difference. We must make it fun, approachable and learnable for so many more people. We must enter this uncharted genre and find the fun and signpost it so that it is easy for those in need of it to recognize the fun in it. (That is all good game designers do.)

Theorists might need it too

I also hope that cohabitive games will be helpful to game theorists or decision theorists, to build intuitions about embedded negotiation. Negotiation is reified cooperative bargaining theory, which drops hints about the ideal shape of preference aggregation. It also might be relevant to extortion resistance and averting extortion races.

There's a really interesting open question: Will advanced technological agencies, starting as separate beings without transparent cognition, converge towards merger, or towards war? I think we really might stumble onto a lot of relevant intuitions in our travels through cohabitive games.

(Also, I just expect them to be good games, this is discussed throughout)

First to Arrive (Confused, Anxious and Lonely)

Every single board game rulebook contains the line "The player with the most points at the end of the game wins." (MostPointsWins). I don't understand why, and I'm not sure anyone does. MostPointsWins makes every game it afflicts into a zero sum game. Cohabitive games, in contrast, are positive-sum, as is real life. The absoluteness of the payouts (Win or Lose and nothing in between3) pretty much forbids negotiation, because it's inherently going to be rare that any two players benefit from following the same plan for very long. If you offer a deal, you must be doing it because it increases your chance of winning, but only one person can win under the MostPointsWins rule, so that deal couldn't be very good for me, and I'll always suspect your deal of being a trick, so in most cases no detailed deals will be offered. That crucial art of weaving agreements that allow us to stably share the world with others is all but forbidden in basically every board game we have.

That probably isn't healthy.

When there's no incentive to make deals, with that you lose an incentive to inquire together and build a true shared understanding of the game within the group. That wedges a hatchet in the head of the social learning process. In contrast, in P1, sharing our understanding of the game was about all we did. That might have had something to do with it being a new kind of game which everyone was very enthusiastic to get to know, but it probably had something to do with the fact that we all had incentives to help our peers to understand what we needed from them and how we'd make it worthwhile for them, or why it would be a mistake to encroach on this territory or that. We benefited from other players knowing more, instead of being harmed by it.

Since learnability is everything, for a game, (and for many other reasons) I expect that cohabitive games will just be better games in general, as it enables far more social learning.

If the MostPointsWins rule is so destructive, why is it so common?

I can think of a lot of reasons, but we'll defeat every one of them:

- When every gain you can make is a loss for others, it infuses conflict and depth and tension into everything, you're no longer just PvEing against a simple set of game rules to gain points, every point contends with other people, who are just as smart as you, and who learn and adapt to your tricks. There's a lot to learn in that.

- Interestingly, a lot of eurogames seem to try to separate players into their own little gardens to reduce this! But they'll still have the MostPointsWins rule in the book! It's really odd! I kind of feel like they keep MostPointsWins as an option. An enlightened player is allowed to just chill out and focus on their own game and still have a good time even as others around them are allowed to sweat and race.

- Ultimately, though, relationships can be much deeper without the MostPointsWins rule, removing it enables open dialog and dealmaking, without forbidding competition. While competition gives you reasons to pay attention to and engage with other players, trade offers way more of that, with probably less stress and tension.

- Tribal hostility. People don't find it intuitive that we could fruitfully coexist alongside groups with irreconcilably different values to our own, or have a healthy, open dialog with them.

- In a highly connected world, simply not interacting with other tribes isn't an option. We have to be good at it, and so we have to find the fun in it.

- It authorizes a common impulse people seem to have to drag others down to make themselves look better. A Eurogame often says, "I know I'm not really thematically supposed to be about dominating others, but I know that you love doing that. So go ahead. I'll give you an excuse by making it part of the rules."

- If you expect nothing but adversity from your coplayers, if the game requires it of them, then you wont be mad when they do it.

- It makes it easier to teach the game, and that is a major factor in a boardgame's success.

- Full article: The point is not to win (The point is to grow), and I'd recommend reading this if you're interested in games or learning at all.

- Summary: MostPointsWins is the norm, it's expected, it doesn't have to be explained. It also makes players' play objectives and real objectives pretty much the same ("win"), which dodges a whole paradigm about the purpose of play. But we are skilled and passionate and so we can just explain that paradigm or convey it in the theme and art. It is typical for high quality video games, which are common today, to assume this paradigm.

- So when introducing a cohabitive game, I ask game hosts to skip explaining the play objective and go straight to explaining the real objective: "The point of the game is to reckon authentically with selfishness and atomization, and then find the social patterns that survive it."

Or maybe I'll write that in big letters on the front of the game box or something so that they don't have to say it.

Playgroups who understand that will understand the game and have a good time.

- Direct violence is the base reality that legal systems address and reflect. So even in a cohabitive game where violence is never the best outcome, it kind of makes sense to start exploring the game, learning it, by just enacting the dumbest violence. So it's inherently difficult to build a coherent game about civic proxies for violence without first building and passing through a game that is just violence, and maybe a lot of game designers just dwell there, because you can find infinitely deep patterns in any adversarial process, and I guess every time your negotiation mechanics break, it reverts to being a game about violence. But we can be more sophisticated, and though the patterns of cooperative bargaining are not natural, they aren't fragile either.

So I can understand why game designers keep doing MostPointsWins over and over but I don't think it's actually good, it seems not fun nor healthy nor lucrative, relative to the alternative. It's just a bad design habit that lines up with pre-existing expectations about what a board game is, which I think people are going to be happy to re-evaluate when faced with novel contenders that actually pull it off and manage to be fun and interesting games.

Enter,

Peacewager 1

Each player controls a pair of characters. Every turn, each character can move one space and perform any of its unique actions, which transform the landscape and affect other characters.

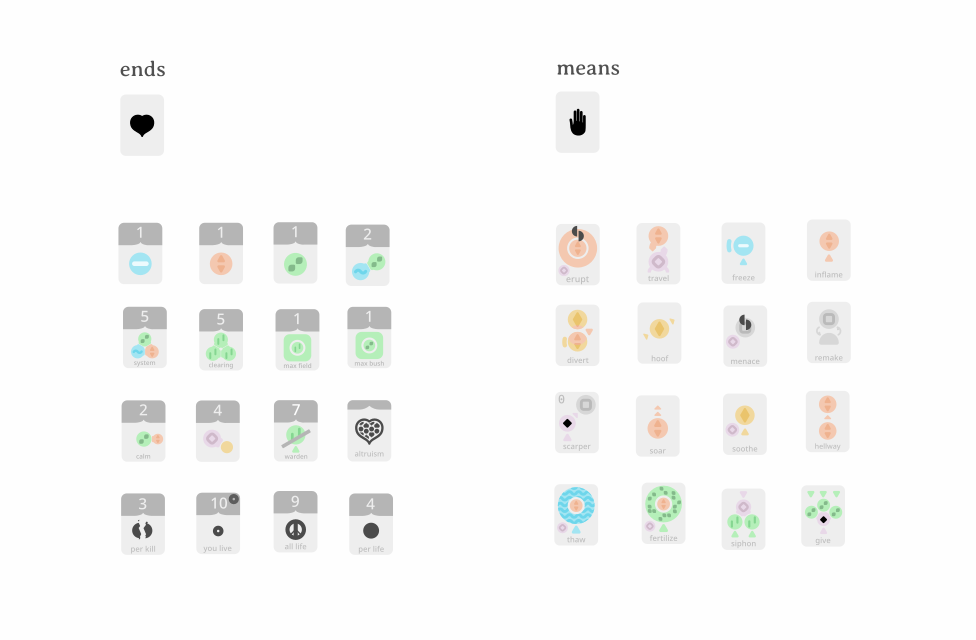

Players have a couple of value cards, which describe ways of scoring, depending on the state of the environment at the end of the game. Crucially, players' values are displayed in the open.

Examples: One player might score a point for each remaining forest, another might score for fields (mutually exclusive), and most characters will lose points for the presence of holes in one area or another. And there can be more complex criteria, like wanting forests that are next to other forests, or volcanoes that are next to lakes, or frozen lakes that are next to both a tomb and a mountain.

These give rise to complex relationships, conflicts and alliances, which in turn give meaning to the landscape. That mountain, next to a lake, isn't just any mountain, it's very important to Isla. If you volcanoize it, Isla might have Dean kill your firstborn. (Dean will do what Isla says because she is the only one who can freeze lakes.)

Peacewager 1. A small map.

The game ends after a certain number of rounds. Players must make efficient use of the time they have.

Your goal is to score high, individually. You should be indifferent to other players' scores, they are not your score. Cooperate when it benefits you. Steal when it benefits you. The goal of the game is to reckon with all of the selfishness and atomization that exists and find the sacred patterns of coordination that survive it.

values and abilities.

(there are a lot more than this, but most of them are just cruddy slips of paper with text printed onto them. For those, I found it was surprisingly crucial to put some colors on them to make it immediately clear which terrain types they concern; it's very difficult to form an understanding of the relationships between players and the land, without that degree of visual legibility.)

A challenging cohabitive game should tilt towards tragedy, it should generate visceral examples of diplomatic failure, irrational wars, costly to all sides, until players learn to coordinate to escape it. Uncoordinated action, by default, should tend to be punished in these sorts of ways:

- Escalation towards mutual destruction. An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.

- Wounds on the landscape as a side effect, for instance, there was an ability that allowed one player to subdue one of the other players' pieces, at the expense of creating a hole tile. Holes harm both players' scores.

- Pyrrhic defeat. A situation where one player refuses to sign a treaty and has to be eliminated by a stronger player. (Elimination is never an ideal outcome for either party. It precludes trade.)

- Impasse. Examples:

- In a simple game where San likes forests and Eboshi likes fields, and each has an ability that lets them flip an occupied forest/field tile, causalist players with no means of coordinating can in some cases become trapped in a cycle of flipping it back and forth. Eboshi flips it to field, San flips it back to forest, and so on, until they run out of time. Whoever stops first in the tug of war loses ground. If there's a lot of ground to be lost, and if there was anything far away that they would have liked to have done (for instance, healing holes), they won't get to do it.

- Where players wish that they could pass each other to access land, but can't trust that the second mover wouldn't kill the first, so their access is restricted.

In P1, players learn that by making sensible agreements they can easily avoid these things. (In future games, I think I'll give the challenge of avoiding these things more texture. More on that later.)

Relationships between the characters of P1 are uniquely rich. The other players are not just obstacles, they're also affordances, you will probably need their help, so try to find something to offer them. Sometimes you won't have anything they immediately need, and instead you'll have something that is wanted by a third person who has something that they need and then things get very intricate.

I think one of the things that made it difficult for new players to connect with the premise was the continuous payout scoring. There wasn't a crisp objective, at the end of a game, the game wouldn't unambiguously tell you whether you had done Well or Poorly, it wouldn't tell you which player was most skilled (because everyone was essentially playing a different game (some goals may be harder to pursue than others, and some characters may be generally stronger, or may score more easily than others)) The game wouldn't even reliably tell you whether you'd improved on your own previous score, since conditions varied so widely between sessions that a mediocre score in one scenario would be impossible in another.

That worked for me, I found a lot of the ambiguity and openendedness of multiplayer outcomes delightful and refreshing, the game didn't tell you how to feel, you had to figure that out for yourself, as it always is in life. (But it is still all clearer than life ever is.)

But I think it's important for learning players to be told what it is they'll learn and how to tell they've learned it. That's what a crisp, binary goal does.

A simple fix for this would be to find a particular score threshold that players will achieve with and only with practice, and tell the player "If you score this high, you've Succeeded (now move onto the next game module)"

I'm very aware that not all numbers will feel interesting or meaningful to optimize, so I tried to make the numbers represent things that people could viscerally relate to, goals like "grow your town", "protect trees", "create habitats for a certian blessed animal", "prevent as many murders as you can" (and the compliment, a novelty character, "do all of the murders").

To facilitate dealmaking, P1 just permits any contract and punishes violations of contracts with the removal of the violator's pieces (death) and the balancing of the violator's score to zero (torture?). On receiving this affordance, we found that we didn't quite know what to do with it, it was too big to swallow in one sitting. In retrospect, it could have been used to instrument systems of extortion ("I hereby enter into a contract where if you do not torch your own mountains, I must kill your elder piece, (otherwise, if you comply, I will not kill it for at least five turns).") I have no idea what I would have done if someone had started using it for that, but no one thought of it! (thankfully?) I remember one playtest session being during an event, and at that event was a particular contract lawyer with a love for shenanigans. I would have loved to see what he would have done with it. IIRC, I don't think I was able to convince him to join on. I should dig into that. The ones who don't show up are often the ones who have the most to tell us.

Would you like to try Peacewager 1?

Edit: It's all been released! https://dreamshrine.org/OW.1/optimal_weave.html

P1 and Friendly Cohabitive could be adapted for very different purposes.

Peacewager 2 Friendly Cohabitive (FC) (provisional title) is being considered for the purpose of gently guiding all sorts of people to let go of eliminationist preconceptions and practice sharing a world vivaciously. No tweak could turn P1 into that, but P1 could be developed into something that is worthwhile in a different way.

Resembling P1, Ritual Cohabitive would be a minimal, probably more abstract stand-alone game for game hosts who already have background in diplomacy. The game would serve a useful ritualistic social function of establishing common knowledge that both players possess an aptitude in good faith negotiation, revealing, pledging that it can be expected of us. Turning the vibe of their interactions up towards confession of difference enabling productive dialog. The sort of thing you'd play a quick round of before penning a deal, or to start a relationship with strong honesty norms. It would be nice for that to exist. P1 could develop into that. I wouldn't recommend it for that yet. Maybe soon. It needs more of a sacred air to it, less bag of parts.

If I focus on this specific purpose, P1 can probably be refined and simplified quite a bit.

Getting cards printed

The cards were printed via MakePlayingCards. I can neither recommend nor disrecommend, they're the first ones I tried, prices seemed good. The print alignment is a bit wonky. Colors aren't very vibrant, but that could just be due to printers and computer displays inevitably having different colorspaces and me not adjusting my graphics for them. The only way you can be sure of what colors you're going to get from a printer is to have them physically send you some test prints.

Friendly Cohabitive. Various thoughts on Next Steps:

- P1 was a bit of a sandbox of generic cohabitive game parts. I don't know if that can work. It requires players to learn a lot of arbitrary information about random glued together characters before every round.

- A game designer's job is to find the fun and signpost it, so we should probably hand-design scenarios that're reliably dense with our best finds.

- I've designed a succession of simple tutorial levels that teach basic lessons like how to avoid impasse, sometimes you have to make an agreement in order to pass by each other, etc, but that kind of thing is way better suited to single-player video games than boardgames, because in a boardgame you have to set up each one of those, and it's not really social, if the game host has been through the tutorials they wont enjoy watching their friend go through them.

- A better approach might be to design a general scenario generator that's good for beginners and okay for advanced players, then when people are reliably scoring above a certain amount, let them graduate to a scenario generator that concentrates trickier dilemmas.

- I need to start thinking about specific characters and specific scenarios. For players to care more about the goals of their own player than those of their opponents, they should be distinct and thematically interesting. (EG, the below Moloch, or Miracle Machine)

- I keep coming back to the archetypes of San and Eboshi from Princess Mononoke. Forager and agrarian, basically. Both sympathetic characters (Yes, there are people who'd play Eboshi :), and if you are reading this, you're probably already on team eboshi irl), despite being in mortal feud. It's a bit difficult, because a big point of cohabitive games is that eliminationism is not the best way for either of you, and at least in the movie, and it was a great movie, seemed like it might have been, so I'd need to rework the archetypes into something less heartwrenching and they could end up being less compelling at that point.

- I can think of another character we might like. The webcomic Unsounded had a great knave in it, Murkoph, who was just straightforwardly a -… let’s just say he eats people, but he does not hide his nature at all, not for a moment. He’s an honest animal, he's very very hungry, he has no choice in the matter. And it was as if his ancestors did not eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, he commits evil innocently, like a beast, or a child, he cannot imagine that he'd be caught. So there is no point in yelling at him when he violates whatever he violates. It’s our fault, for not having killed him yet, or for leaving his cage open. He's pathetic, really, his visible incapacity to hold ot a contract actually makes him very vulnerable. Like Parfit’s hitchhiker, he already regrets his inevitable future actions and fears their deserved consequences. He teaches us the weakness of the uncontractable.

- A game designer's job is to find the fun and signpost it, so we should probably hand-design scenarios that're reliably dense with our best finds.

- Nothing unites factions like a common enemy. Having one player who's a clear existential threat to everyone else will remind even very bitey players that they must find balance between pure cooperation and all-against-all deathmatchism. It can give a face to the game's coordination problems.

- We could just straight up call a common enemy character "Moloch" (moloch is the personification of negotiation failure) and give it powers oriented around sowing seeds of division (temptations, weapons that can only be used to harm our own, disruption of coordination infrastructures). If that won't get players to realize that the real enemy in life is war itself I don't know what will.

- Another character concept: "Miracle Machine." At first able to offer great riches to all parties as a trading partner, Miracle Machine constantly threatens to take off and grow exponentially. Players will be tempted to make deals with the MM player for a growing array of applications, but they must keep it carefully contained, because MM will never stop asking for more space, and left unconstrained it will inevitably grow to such a size where it no longer needs to ask permission. Push your luck!! :D

- (Sama turning a big dial that says "capabilities" on it, constantly looking back at the international anti-proliferation community for approval like a contestant on the price is right)

- Work just as hard on supplementary materials. Documentaries and demonstrations of cooperative bargaining concepts like prisoner's dilemmas, pareto frontiers, and if we can, Diffractor's equivalence. The game is far more meaningful and will probably have much higher skill transfer if the player knows about these things. Maybe do it by fitting these things into the lore. Invite serious play.

- There was a principle that came up early in the design in P1 but wasn't kept: I wanted to make the game more approachable by making the basic individual goals fairly rich on their own: It should be an interesting little challenge just to get around the environment and maximize your own score within the time available, even when you are alone. This would ensure that players will immediately see that there was a game here, even if they don't have a sense for systematized negotiation. Then the rest of the game would reveal itself as they started to notice other players and how they could interfere, or help. Very early prototypes had this. Each world generation would be an interesting little puzzle. It was cool. It introduced unnecessary complexity, as negotiation is complex enough, even with very simple natural laws, so simple natural laws were favored.

I'm not sure whether having it both ways is possible here; It requires us to find rules that don't distract from learning in the social context, but which also give rise to interesting challenges in the asocial context. Unlikely. Maybe we should give up on this one. - Instead of P1's omniscient contract enforcement system, which may be too open-ended to be learnable, I'd like a study of the practicalities of establishing contract systems using the flawed material instruments of our cruel earth: Fences (good fences make good neighbors), monitoring, arms control, and dynastic marriage.

- Let us build a strand-type board game, where weapons are more boring than laying the infrastructure of peace.

- I've heard it suggested that if we got world leaders to dose MDMA together there would be no further wars. I don't know whether that's true, but there's a lot of stuff like that. The compassion drive, ideally, takes your partner's wishes and makes them your own, which would be an elegant way to realize a truce. Social technologies that work in that way — dynastic marriages, mergers, or value aggregation — could be modeled exactly with an item in the game that lets players alter their win condition to include the conditions of other players, tying them together, facilitating absolute trust. In P1, that item was implemented with an ability to simply add another player's score function to your own, which would always result in the user getting a "higher" score at the end, so, these abilities would have to be labelled with warnings about the dangers of wireheading, explaining that there is an important difference between maximizing your score, and maximizing the things in the world that the score describes. This is a subtle distinction, I'm not sure every human cares about it, and I'm not sure how to formally define it without assuming a fixed ontology (which neither humans nor AGI do). So it might not be possible to explain it succinctly enough.

- But I'll make an attempt, tell me if these thought experiments make the distinction clear:

- If you initially score for forests, and you're being offered the ability to score on fields as well, which would then make you pretty much indifferent to forests (fields are the flip-side of forests), one who carries the virtues of a survivor would reject the offer, because if they were made indifferent to trees, fewer trees would be saved, and they currently actually care about the trees, so they would like to keep caring about them. Accepting the new scoring rule would change who they are so drastically that it would not be very different to death.

- If you want your friends to be happy, and you were offered the option of entering a permanent delusion where your friends were always happy, and you no longer had to do the work of helping them and protecting them from the dangers of the real world, you would probably reject that. You care about whether your friends are actually happy, in real life. You don't just care about your experience of the situation, you care about the actual situation, the external reality, how other people are really doing. There is a difference.

- Taken to an extreme, this would just dissolve the game into a purely cooperative one. It's more interesting in cases where the merger cannot be perfect, or where it's only available between some players and not others, but mostly it will just have to be a novelty.

- But I'll make an attempt, tell me if these thought experiments make the distinction clear:

- Give some players a binary success/fail goal instead of just a score goal, just difficult enough to be achievable with exercise.

We may still be able to retain some differentiability here: Clear probabilistic factors in success (eg, items that help only some of the time, which they should collect many of), and the success of the group — the number of players who were able to meet their goals — could be another continuous measure of the negotiation skills of the group.-

I notice that "More than one person can Win" is much easier to communicate than "You should maximize the expected value of your score rather than your expectation of getting the highest score (and yes those are somehow very different things)". My finding is that as soon as you show a gamer any scoring system, their eyes turn red and they start machinating under the assumption that the MostPointsWins rule is in play, it's close to hopeless.

-

Cohabitive games that aren't board games

I'm not sure whether I want to keep working on physical boardgames. I actually don't play them very often. But also, digital online games are more flexible in a couple of ways.

There are reasons the physical format is less limiting than you might expect, boardgames are very good. A boardgame requires the rules to fit in the players' head, but that's also just a pretty decent account of good game design: accessible strategic depth, the laws of those arenas of maximum fun, where we can most easily learn to generate complex strategies, must necessarily be able to fit into the player's head. Physical boardgames also require players to physically get together around a table, but that's also currently the only way to get top quality conversations. Both of these things are really well suited to cohabitive games, conversation is crucial, and negotiation is far more tractable when the rules of the world are simple and legible.

But the board game medium is still somewhat limiting. It imposes constraints on board size, setup procedure duration, and cleanup, and upkeep, and the number of calculation steps involved in scoring rules. This all makes it harder to model real systems. Physical presence isn't the only option, too: VR does promise a quality of shared presence and conversation that digital experiences haven't had before. But VR won't be good enough for this for a few years (it's currently too low-res, or too expensive), and I don't expect it to become ubiquitous enough for VR tabletop games to see wide popularity until a few years after that.

And if we start thinking more in the domain of video games, we can imagine very different kinds of cohabitive games.

A lot of online multiplayer games rest on the appeal of their character design. Think of Smash Bros, Overwatch, or League of Legends. Characters' unique abilities give rise to a dense hypergraphs of strategic relationships which players will want to learn the whole of.

But in these games, a character cannot have unique motivations. They'll have a backstory that alludes to some, but in the game, that will be forgotten. Instead, every mind will be turned towards just one game and one goal: Kill the other team, whoever they are. MostPointsWins forbids the expression of the most interesting dimensions of personality.

So imagine how much richer expressions of character could be if you had this whole other dimension of gameplay design to work with. That would be cohabitive.

This too might have to wait for VR, though. When different characters have such different intentions, where each new matchup adds up to a new game, conversation might be strictly required to collectively make sense of the situation and avoid collapsing into a boring kind of chaos. That would require good voice audio quality. Players wont reliably have good voice audio gear until VR is popular. I'm not sure, though. It might also be the case that since you actually do know other characters' motives, and you can try playing as the other characters, that could foster enough empathy, and explicit communication wont be needed (beyond simple signals like "let's cooperate", pointing, and maybe a system for addressing violations of expectations?). I'm a little bit surprised that competitive character action games work at all without voice audio, from what I can tell (?) they do, so pre-VR short match character cohabitives might work fine as well. (But I don't expect I'll be able to make one in the foreseeable future. Very open to part time roles in collaborations though.)

The development of Ritual Cohabitive, and Negotiable Cohabitive is likely to proceed pretty slowly. If anyone would be interested in developing (or already is developing) a negotiation game of your own, I'd love to know you, and I'll try to support you! Join the element chat and we'll get started.

mako yass. September 2023.

I think there are eurogames that can be played as if they were cohabitive (please reply if you can think of any that work perfectly with the MostPointsWins rule removed), but the ones I've seen were not designed for it and they don't encourage or support it. It really seems like I'm the first to turn up. I'm not feeling triumphant about that, I am feeling more, confused, anxious, and lonely about it.

There are some video games that might qualify, games like Ark or Rust, but they tend to collapse into factional eliminationism and negotiation dynamics tend to be blighted with griefing. Motives are usually ambiguous. Negotiation comes almost accidentally.

footnotes

-

The name "cohabitive" was introduced by Skyler. I decided it was a better name for the genre than the one I was using before, and I've signed on with it. ↩

-

It's true, as far as I can tell, there really are no other board games like this today. There are semi-cooperative games, but they're all hidden motive games, where players' unique agendas are kept secret (a highly recommendable example is Nemesis), either of which make negotiation impossible. ↩ ↩2

-

I've heard objections like, no, losing isn't a zero payout, there's better and worse loss outcomes: coming second is better than coming third, losing by a hair is better than losing by a lot. I guess that is valid. I don't know how many players see the MostPointsWins rule this way. It's still presented as zero-sum, though. So finding that most resilient peace in these games is still going to be impossible almost all of the time. ↩